Antisemitism and the weaponization of story

Or, why higher ed's hate problem is a story problem

Happy new year, everyone! I hope you had a restful holiday season with loved ones, and that your 2024 is beginning beautifully.

My own holiday season was quiet and peaceful and full of family time. It was also filled, I confess, with endless X / Twitter refreshes as the presidents of Penn, Harvard, and MIT committed professional suicide while testifying before a Congressional committee about the explosion of antisemitism on campus. Penn president Liz Magill, MIT president Sally Kornbluth, and Harvard president Claudine Gay were asked repeatedly to acknowledge and condemn the vandalism of Jewish dorms and Hillel houses, the hijacking of classrooms and communal spaces by antisemitic groups, the loud calls for genocide, and the unchecked terrorizing of Jewish students — not only by other students, but also by faculty. They couldn’t do it. Instead, they regurgitated technocratic bullet points — callow evocations of context, hollow defenses of free speech — at the very moment when they should have shown leadership.

One would think that at least one of these women would have absolutely burned with clarity in this moment, that she would have leapt at the chance to speak the truth, name wrongs, and chart a better future. But none were willing to call hate by its name. Not one would condemn it. They rationalized, they made excuses, they were, in the words of a subsequent bipartisan House resolution, “evasive and dismissive.” It was total Hannah Arendt territory: the banality of evil as exemplified by a trio of middle-aged academic bureaucrats, women who began their careers as scholars but became, over time, useful idiots. They were trained as thinkers, but somewhere along the line, they traded reason for ideology, and became servants of a deeply pernicious agenda. Liz Magill resigned within days. Claudine Gay held on for a few weeks and then stepped down amid a plagiarism scandal. Somehow, Sally Kornbluth remains in her post.

I am just about their age, a little bit younger than Magill, a little bit older than Gay. And I once taught at Penn. I left because I felt the culture of academia, once a welcoming and wonderful home to me, beginning to eat itself alive. It took a bite out of me — a story for another time and place — and I got out before it could consume more of me than it already had. That was nearly twenty years ago. Now, watching these women presidents ruin themselves on the national stage, I wondered: If I had not left academia, if I had stayed and worked my way up the bureaucracy, as one does, would this have been me? Would I have had as much trouble with the truth as these women were having? Would I, like them, have lost my reason? Would I have become an apologist for hate? These women were not born this way, after all. They are products of their environment, highly successful creatures of an academic culture that has badly lost its way. Their careers speak to how good they are at becoming what the academy requires them to be — even when the price of becoming that thing is one’s own humanity.

Amid the holiday turkeys and roasts, the long lazy stretches of family time, the gifting and the tippling, the laughter and the talk before the fire, amid, in other words, the straight-up uncomplicated love of the season, I found myself thinking about hate — about how we learn what hate is, about how the idea comes into focus in our minds as we grow up, about what kinds of things can make us lose the moral clarity that allows us to see hate for what it is. I thought about how the spike in campus antisemitism has exposed our polarized culture’s uneasy relationship with hate — our willingness to tolerate certain kinds of hatred of certain kinds of groups in the name of tolerance. And I thought back to my own childhood.

I. Dish Soap and Dying Paperbacks: Early Lessons in Hatred and Compassion

A memory: One day, when I was around nine years old, I was squabbling with a little boy. He baited me and bested me, and I lost my temper. “I hate you!” I yelled, loud enough for a Responsible Adult to hear. Squabbling was strictly off limits, and there would be consequences. But even more off limits was my use of the word “hate.” “Never, ever, ever use that word toward another human being,” the Responsible Adult instructed me, and then proceeded to wash my mouth out with soap, as if the hatred I had just expressed still lingered on my tongue like a deadly poison. Responsible Adult scrubbed away all traces of hate, lemon dishwashing liquid replacing the word’s rotten flavor with the soapy taste of redemption. Washing the mouth out with soap was a common punishment at the time — used widely in families and even in schools — and it worked. To this day, I have never told another human being that I hate them, never spoken of hating another human, never even thought it. I’ve had plenty of negative experiences with people and I’ve got the negative emotions to go with them — but they do not resolve into hate. They just don’t.

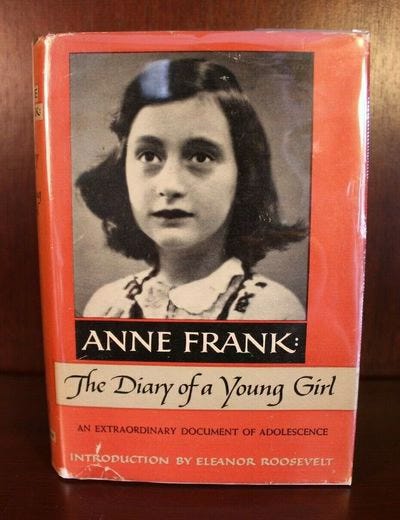

Another memory: Around the time I learned not to say “I hate you,” I ran out of books to read. I had read all the kid-level chapter books in the school library, the local branch, and the bookstore. I’d done all the available Judy Blume and whatever other YA was around, which was not much in the late ‘70s. I was a reading tween, ravenous for words but not yet ready for grown-up writing. My parents had walls and walls of books and they were all open to me. I would sit on the floor scanning the shelves, pulling things out at random, looking inside for language I could get lost in. Lytton Strachey’s Queen Victoria. NOPE. James Clavell’s Shogun. NOPE. Mom’s medical books, with the mesmerizing pictures of diseases — fascinating to look at, but not good reading material. It was a frustrating time. One day, a crumbling paperback spine caught my eye: The Diary of a Young Girl. I pulled it off the shelf and it nearly came apart in my hands. The paper was brittle and yellow, the cover hanging by the barest hint of brown glue. A black and white photograph of a young girl gazed up at me from the cover. This was Anne Frank. I had never heard of Anne Frank but I was instantly sold on the thought of reading an actual diary of a girl not much older than I was. I opened the book and began to read.

Extremely expensive first edition — not the one I found on the family shelf, but similar!

I was with Anne from her first entry, on her 13th birthday, on June 12, 1942, during the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam. I was with her when, a month later, Anne and her family went into hiding after her sister was ordered to report to a Nazi work camp. I was with her during her two years in hiding, years when she gets her period, when she falls in love, when she decides to be a writer. Anne’s last entry was on August 1, 1944. In it, she describes herself as “happy on the inside,” and reflects on how different our public and private selves are. She wishes she could be her true self with others, and writes about how frustrating she finds people, with their expectations, judgements, and interference. She writes of “trying to find a way to become what I’d like to be and what I could be … if only there were no other people in the world.” In other words, she is a typical teenager with a classic case of the junior existentials. She’s been living in cramped, crowded, hidden rooms for two years; she has not been outside or had a moment to herself. And yet she is still intensely, vitally alive, thoroughly connected to the world, bent on figuring out who she wants to be in a future she very much believes in. The diary ends there. Three days later, the Afterword informed me, she and her family were arrested. They were sent to Auschwitz and then Anne and her sister were transported to Bergen-Belsen. That winter, Anne’s mother starved to death; a few weeks later, Anne and her sister died of typhus, their bodies dumped in a mass grave. On April 12, 1945, British troops liberated Bergen-Belsen. The free, open future Anne Frank dreamed of had come at last — but it arrived too late for her to meet it.

My nine-year-old heart broke. I couldn't believe it. There was no way this was true. I checked with my dad, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of World War II. He confirmed it: Anne Frank was real, the Holocaust happened, the camps, the gas chambers, the starvation, the lampshades made of human skin, all of it was real. I remember checking with him a second time about this last one. It was so incredible, so gratuitously grotesque. Who even imagines doing something like that? And what sort of a person turns that imagining into something real?

I struggled to accept that these things happened, that people did these things to other people. I didn’t want any of it to be true, but I knew it was, and I had to find a way to hold that in my mind. I cycled through nine-year-old versions of horror, outrage, sadness, helplessness. I wrote about it in my little blue diary that locked with a tiny key, listing off all the things the Nazis had done, bearing witness in my little girl way. “Hitler made lampshades out of people’s skin,” I concluded. “I’d like to make lampshades out of his skin!”

Looking back, I think this must have been my first encounter with mass organized evil, my first reckoning with how totally depraved humans can be, and with how tremendously destructive hatred is when it goes unchecked, when it takes over institutions and becomes the mission of nations. Vengeful fantasies of turning Hitler into furniture aside, it was also a powerful lesson in compassion.

II We Suffer from Chronic Compassion Deficit

Compassion comes from Latin and it literally means “to suffer together with.” In its simplest definition, compassion is what we feel when we notice the suffering of another and wish to relieve it. The Stanford Center for Compassion and Altruism Research notes that compassion is a deeply social emotion, associated with kindness and altruism, on the one hand, and with acceptance on the other — after all, not all suffering can be relieved.

Compassion, like all emotions, has a neurology. We are wired for it, and it is present in its purest form in babies. Researchers have found that babies reliably prefer prosocial and kind behaviors. In a study done at the Yale Infant Cognition Center, infants ranging from 6 to 9 months in age watched a puppet show in which one puppet tries to climb a hill, another pushes it back down, and a third helps the fallen puppet go back up. When asked to choose their favorite puppet, the babies chose the helper. This preference for kindness carries into childhood — with a catch. By the age of four or five, University of Queensland researchers found, kids will choose to help another — whether an adult or a puppet! — as long as it doesn’t cost them anything. If they have to give something up — in the study, they had to give up a sticker — the calculus changes. Kids become reluctant to help when there is a personal price attached, even if the price is small and the person or puppet is in clear distress. By adulthood, compassion has become extremely complicated and murky ground. When confronted with suffering, we are less likely to help another person than a toddler is. And we are far more likely to judge, blame, rationalize, ignore, and generally harden ourselves to what we are seeing. Stanford professor James Doty says this is because most of us live in states of more or less chronic stress and anxiety, which in turn reduce our capacity for compassion. It’s basic chemistry: stress hormones are different from love hormones. When we are swimming in the one, we can’t swim in the other.

Compassion is a critical human emotion, immensely important social glue for families, friendships, and communities. It brings us close in our relationships — and it also ensures that we care for strangers. And yet, we unlearn compassion throughout our lives. We feel compassion with ease and without cynicism when we are babies, before we even know what we are doing. The older we get, though, the less available compassion becomes. We lose touch with a primal neural pathway, with the emotion that moves us to help and to give, to ease the suffering of others, to do no harm. And that is a very big problem. The less we can access feelings of compassion, the more easily we tip into hate. Hate, as I noted in this post, marks the moment that we cease to see others as human — and when, as a consequence, we give ourselves permission to treat people as objects, to destroy and dispose of them. When hate becomes a normalized emotion, when it comes to define group identity and action, as it does in our system of lethal mass partisanship, as it does in the antisemitism that has been unleashed on campus since October 7, we are in extremely dangerous territory.

What can we do to counter hate? Is there a way to short-circuit it? Can we write over it with better code?

III Story Unlocks Our Capacity for Compassion

If my own experience means anything, something that can offset hate is powerful early experiences of uncomplicated compassion. I struggle as much as anyone with day-to-day strain, with the way stress and fatigue and overwork and distraction and worry can harden us to others, not to mention ourselves. And yet, I have never lost touch with how I felt after reading Anne Frank’s diary — with the pure, deep welling of feeling for an innocent girl who deserved to live her life, and very much did not deserve what befell her. I felt it thirty-some years after Anne died, as a nine-year-old girl with no meaningful knowledge of history, and no real experience of the world. I felt it across time, culture, and space, from the snug safety of my family’s limestone ranch house in suburban Indianapolis. And it didn’t cost me a thing. I didn’t have to give anything up in order to choose compassion. I felt it through reading, freely and easily; compassion became available to me through the alchemy of story. I spent time inside Anne’s head, reading the private thoughts she wrote down for her eyes only, and it changed me.

Neurologically, we now know, when I read Anne’s diary, I spent time as Anne. In my brain I became Anne Frank while I read. My emotions mirrored hers. I lived with her, she came to life in me, and when her life was cut short — when her story broke off — I experienced a breaking, too. It was obviously nothing like what Anne experienced. It was also, obviously, exactly what nature intends story to do with a young brain: enable it to experience pure, uncomplicated compassion for another human being. To this day, that feeling is with me. I am as jaded and cynical at midlife as anyone. But that nine-year-old girl is still in me, and I can still access her feelings of compassion. Reading Anne Frank’s diary when I did was a formative neurological experience for me, one that has helped me to keep in touch with how important it is never to dehumanize another person, always to seek to understand their point of view, never to give in to the temptation to hate, always to seek compassionate connection with others.

IV Story Can Also Create Hate

Today, a growing number of young people think that the Holocaust didn’t even happen. Last month, as Congresswoman Elise Stefanik grilled the presidents of Penn, MIT, and Harvard about the genocidal rage running rampant on their campuses, The Economist reported that one in five Americans aged 18-29 “think[s] that the Holocaust is a myth.” Another 30 percent “do not know whether the Holocaust is a myth.” In other words, half of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 doubt or disbelieve that the Holocaust happened. That word “myth” is instructive: if the poll is accurate, 27 million young American adults believe the Holocaust is just a story, a fiction that not only should not be believed, but also should be understood as a manipulative lie, as a mechanism for propagating misinformation. Calling the Holocaust a myth is, in this sense, a very clever way of shorting our empathy circuits. If stories activate the brain’s empathy centers, stories that have been labelled as lies will shut them down. Even stories that are demonstrably true.

The Economist blames social media for this, noting that that fake news is rife on social media, that a third of Americans aged 18-29 get their news on TikTok, and that young people who use TikTok are “more likely to hold antisemitic beliefs” than those who do not. Clearly that’s part of the problem. There is also the problem of what is actually taught in school. Harvard professor Steven Pinker says the explosion of virulent antisemitism on campus is a simple case of “reaping what we have taught.” The American education system has been hijacked by “merchants of hate,” he writes. It’s endemic in higher ed, and it permeates K-12 education. The results are as predictable as they are pernicious. As NYU professor Jonathan Haidt puts it, “If you teach students academic theories that encourage them to hate groups and countries, you get students who can quickly learn to hate groups and countries.” Hate begets hate, and hate education in this country begins very early indeed.

When I was a kid, Anne Frank’s story schooled me in compassion: it opened my eyes to one of the worst episodes of human history, forced me to reckon with terrible truths, and made me contemplate, at a very early age, the importance of recognizing that hate is real, dangerous, very easy to get caught up in, and very easy, too, to justify or deny. Today, the Holocaust is being used to teach kids the ways and means of hatred — how to feel contempt for people, how to reject the historical record in order to preserve that contempt, how to stoke anger and blame and outrage, how to dehumanize entire populations, how to behave toward those that are viewed as less than human. Another way of putting it: the Holocaust is being used to override kids’ natural, hardwired inclination toward compassion — and to cultivate in them an ease, even a talent, for hatred.

British journalist Melanie Phillips calls this “the manipulation of innocence.” And the primary weapon in the manipulation of innocence is storytelling. Story is a powerful tool. It is politically neutral – and politically available. Bad actors around the world understand this, and are using story as a form of terrorism. As Brad Allenby and Joel Garreau argue in “Weaponized Narrative Is the New Battlespace,” Russia, the Islamic State, and others have had great success getting Americans to believe false stories, and in using those stories to turn us against one another — so much so that weaponized narrative is now recognized as a “deep threat to national security” with an unparalleled ability to “undermine an opponent’s civilization, identity, and will by generating complexity, confusion, and political and social schisms.” The spineless inability of elite university presidents to call out antisemitism, the proudly murderous chants of deluded students who truly believe they are on the right side of history, the hijacking of the curriculum by “merchants of hate,” the widespread belief, stoked by schools and social media, that the Holocaust is a myth — these are the signs that we are under narrative attack. They are what happens when storytelling is used to “undermine” a society, “generating complexity, confusion, and political and social schisms.”

If we want to fix our hate problem, then, we have to fix our story problem. We must reclaim storytelling, wrest it from the myth-making of hate and put it to work on behalf of truth. We need what we might call a restorative storytelling — storytelling that restores history, restores fact, and with it restores our rightful relationship with one another, a relationship of compassion, peace, and care, rather than hostility, violence, and hate.

In my next post, I will offer a case study of restorative storytelling through film. More soon!

Anyone who is interested in what happened in Germany should read the memoirs of Sebastian Haffner, who came of age in that country between the wars. My review:

https://ricochet.com/875108/how-a-country-abandoned-law-and-liberty-and-became-a-threat-to-humanity/

Another attack on art in a museum by 'activists', this time soup thrown on the Mona Lisa. Reminds me of what Haffner said about people who needed political activism and chaos to give meaning to their lives.