Best of 2025 So Far, Part One: reading toward a post-partisan world

Five books I loved, that I hope you'll love, too

I’m about to share my favorites reads of 2025 — so far —with you. But first, a short manifesto on why reading matters, because I can’t help myself.

I. A short manifesto on why reading matters

We live in a moment when reading is becoming a deeply political act. In an age of planned distraction, where our attention has been commodified and our focus is being stolen and sold for the tremendous gain of others, reading constitutes a profound form of resistance. When we read anything of significance and length – a novel, a work of history or popular science, a biography or an intelligent self-help book, a 10,000-word think piece, the Bible, the encyclopedia, anything with a brain behind it – we are reclaiming our attention for ourselves. We are asserting our right to control where we put our focus, our thought, and our care.

When we read, we're disconnecting from the pervasive switching culture of short videos, reels, and threads, abbreviated tweets, push notifications, text messages, bottomless inboxes, and the tidal wave of flotsam that pollutes the infinite scroll. When we read, we are training our minds on a single thing, devoting ourselves to the special work of following the progress of someone else's mind as they work through a complete idea.

Reading is a gesture of reverence and always has been. Today, it is also civil disobedience, a powerful peaceful protest against the fragmentation and loss of focus that are the ruinous products of our always-on information age. Concentration is the new refusal to conform to the pernicious social and political expectations of a world warped by fake news and riven by digitally-induced mob behavior: It is how we maintain ourselves as selves, and it is what we must do if we want to lead any sort of intentional life, or form any sort of meaningful connection with others. In our ever-polarized world, concentration is the precondition for cultural repair.

So! In the spirit of reading toward a better life and a better world, I wanted to share a few books I’ve read this year that I loved, along with a little bit about why I loved them.

II. Books I’ve loved this year, and why I love them

Richard Flanagan’s Question 7. I've been a fan of Richard Flanagan ever since I picked up Gould’s Book of Fish in a London book shop twenty-some years ago, hauled it off to Ireland in a prohibitively heavy suitcase stuffed with way too much reading material, and then devoured it, along with way too many cups of tea and way too many digestive biscuits, in a little cottage in the back of Donegal’s gorgeous beyond.

Question 7 is part memoir, part postcolonial historiography, part literary analysis. Flanagan begins by trying to piece together his father’s time in a Japanese POW camp during World War II — an endeavor that is doomed because even if we can go to the place, the place can never tell us its secrets. The attempt leads, however, to some absolutely magisterial writing about the power of storytelling — not only to change how people think, but also to drive what they do.

Flanagan convincingly argues that the novelist HG Wells essentially invented the atom bomb, a finding that begs all sorts of questions: Can a novel alter the course of history? Yes. Can a novel start a war? Yes. Did a novel invent the the nuclear age? Yes. What is the moral status of this power? Is it bad? Good? Both? Neither? Other? Yes.

John O’Donohue’s Anam Cara: A Book of Celtic Wisdom. John O'Donohue was an Irish Catholic priest and philosopher-poet who found a way to write about the terrain of the soul that was at once deeply spiritual and not remotely doctrinal or ideological. He writes for nonbelievers and skeptics just as much as he does for people of faith, and the most beautiful thing, for me, about his work is how he offers resolutely secular people a language for thinking about the deepest, most personal aspects of life.

“Your soul knows the geography of your destiny,” O’Donohue writes; “it will teach you a kindness of rhythm in your journey. … The signature of this unique journey is inscribed deeply in each soul. If you attend to yourself and seek to come into your presence, you will find exactly the right rhythm for your own life.” If you don't, “you can perish in a famine of your own making.”

Every sentence is a poem. O’Donohue is worth reading slowly and contemplatively, when you have time to go over his words again and again.

Sarah Wynn-Williams’ Careless People. This is a jaw-dropping memoir about working at Facebook during the years that it effectively became a global superpower. Wynn-Williams understood that Facebook was a communication revolution that would have tremendous geopolitical impact long before Mark Zuckerberg did. She talked her way into a job at the top levels of the company and worked alongside Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and other top execs as Facebook became a major international player. She was horrified by what she saw. In Careless People, Wynn-Williams reveals what she saw to the world.

In the course of the memoir, we not only learn about the toxic work culture at Facebook, but we also learn about the kinds of deals Facebook was making with foreign governments, up to and including deals with China that put US national security at risk, while also making Facebook a willing partner in the Chinese government’s repressive surveillance of its citizens.

I cannot cheer loudly enough for Wynn-Williams, who had to break a non-disclosure agreement with Facebook in order to tell her story. I also cannot cheer loudly enough for Macmillan, which published Careless People knowing it would face the full legal force of a trillion-dollar company bent on burying the book along with Wynn-Williams and her publisher.

We all have the right to tell our stories. No one else can own them or tell us what to do with them. Increasingly, though, employers try to do just that with overbroad NDAs, lopsided non-disparagement agreements, and severance agreements that are actually punitive perpetual gag orders that seek to silence people for life.

This is not "confidentiality." This is not "protecting trade secrets." This is subjugation and the only way to end it is to do what Macmillan and Wynn-Williams are doing. This is a subject that is close to my heart, and this is a book that gives me hope.

Ann Jones’ Women Who Kill. This 1980 classic is a survey of American history through the lens of women murderers. First paragraph:

“Five years ago in a women’s literature seminar, a student depressed by reading The Awakening, The House of Mirth, and The Bell Jar complained: “Isn’t there anything a woman can do but kill herself?” To lighten the mood I quipped, “She can always kill somebody else,” and realized in the instant that it was true. I have been working on this book ever since.”

This is history done right — it’s deep, it’s thoughtful, and it’s on fire. It’s looking to the past to explain the present, and it's also showing us the present in a way we have not yet seen it. For example, Jones reveals that in Puritan New England, women had rights that were later revoked, including some we have not yet recovered: In a number of colonies, women earned equal pay for equal work. They could own property, vote, hold office, and serve as jurors. They could also get abortions without breaking the law. This information made my head spin when I first read it. It's still spinning.

Women Who Kill is as revealing as it is perverse, and offers an unforgettable look at who we are and how we got this way. It's angry but controlled, smart but accessible, and it has a wicked, witchy sense of humor. It feels fresh and relevant, despite being nearly half a century old — not because of the focus on killing, but because of how wisely it reveals the progress of misogyny in a world that claims to have moved beyond it, but in reality keeps finding new ways to reinvent it.

I haven't enjoyed a willfully eccentric work of US history so much since Sarah Vowell's Assassination Vacation and Tony Horwitz's Confederates in the Attic.

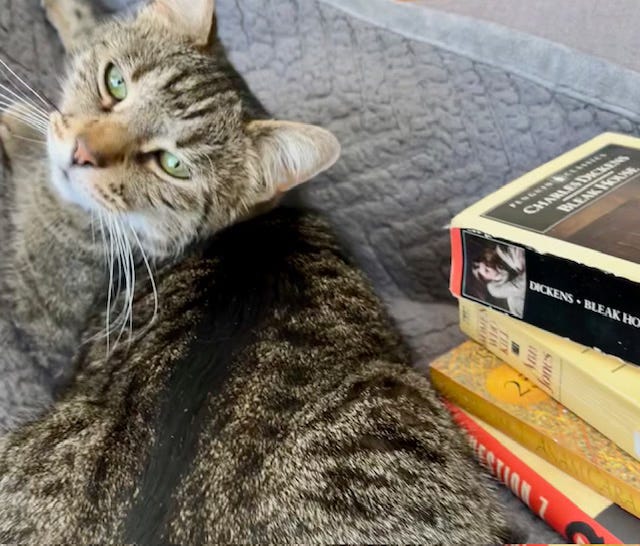

Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. I have lost track of how many times I have read this book. Nor do I know how many times I have taught this book. This winter, it came to me that I would like to revisit Bleak House. And it came to me, too, that I wanted it for a very specific purpose. I wanted it for nights when I can't sleep. I wanted, on those nights, to be able to listen to Bleak House — I wanted to be read to. So I set up a little Alexa by the bedside, and found a free Audible version of Bleak House, read by the immortal Miriam Margolyes, and then set about spending time with Dickens during my insomniac hours.

I cannot say enough about this experience. I've only ever read this book quietly inside my head. I've never actually heard this book. It was immediately clear to me, from the moment I began listening to Miriam Margolyes in the middle of the night, that this book was meant to be read out loud, and that its audience is ideally an audience of listeners.

I know this great old novel by heart. But I'm getting to know it in a new way now, and this in turn is allowing me to get to know Dickens differently. I won't get into details because that's a post in itself for another time. I'll simply say: try this. Let yourself be read to — if not in the middle of the night, while you're driving, while you’re scrubbing the bathtub, while you're taking a walk. Being read to is a different kind of reading, requiring a different kind of attentiveness, and a different sort of concentration. It's a listening meditation, and it, too, is a dying art, an essential skill, and, hence, a revolutionary act in its own right.

III. Please share!

So that's me so far in 2025 – the highlights of my reading life revealed. These are the books I'm choosing over distracting screens, the quiet places where I practice paying attention to things that matter, and where my life is endlessly enriched.

Maybe you'll find something here that you will love, too — and maybe, just maybe, you'd like to share your own recent favorites. Please feel free to do exactly that in the comments!

Reading is so fulfilling and illuminating.

Books transport me to different times, places and, most importantly, into the minds of others. Reading lets me delve into how people think and act, why they do what they do and why the world is the way it is or could be. The setting and personae are limitless. We all bring the cumulative complexity of our lives to the book we are reading. This makes every read an intimate and unique experience as you process the lives and world the author take you to. Even rereading the same book is enriching because time changes us so we process the same book with an evolved perspective.

These all sound like great reads! You may have even convinced me to go back to Dickens....