Ann Arbor, 1995: I am sitting in a small arthouse theater, waiting for the movie to start. It’s called Muriel’s Wedding. I don’t know anything about it. I don’t need to. I am here because my friend invited me, and I said yes because I anything is better than staring at the computer screen, blocked and stuck, trying to find the words that will cover the pages that will allow me to finish my dissertation. Any invitation from anyone to anything at all will do.

The lights dim, and the film begins. It’s set in an imaginary Australian town called Porpoise Spit, and it’s about a young woman who wants ever so much more than she can have in this place, among these people. Muriel — played by Toni Collette in what would be her breakout role — is awkward and unhappy. Her “friends” bully her and her father belittles her. She tries to see the bright side, but there really isn’t one, and she winds up hiding in her bedroom, numbing the pain by cranking up the volume on her small pink boombox. Her drug of choice: ABBA, the Swedish pop band that ruled the charts from 1974 to 1982.

This is years before Mamma Mia! rebooted ABBA for the millennium, and ABBA is most definitely not cool. Neither is Muriel; her musical taste proves it. “We’ve told you a thousand times how to wear your hair, but you never listen,” her frenemies tell her. “You don’t wear the right clothes. You’re fat. And you listen to seventies music.” Muriel’s very being is an assault on their self-appointed awesomeness. They cannot be associated with her. “You bring us down,” they shout, banishing her from the group. “You embarrass us!”

Yikes. I, too, have a soft spot for ABBA. Growing up, my father had an 8-track tape of ABBA’s greatest hits, and for years it played on repeat in his huge Chevy Caprice station wagon, which we nicknamed The Love Boat. ABBA was the family soundtrack, accompanying us everywhere we drove. My father was especially fond of The Name of the Game, and I can remember him happily nodding to the beat as he steered us to softball tournaments and soccer matches all across the midwest. The thing about ABBA, though, was that you did not admit to liking ABBA. You did not admit to even knowing ABBA, even though everyone who ever turned on a radio in the 70’s knew ABBA. They were inescapable. I secretly adored ABBA. I especially adored Dancing Queen, the song Muriel loves most. But that was a forbidden, unspeakable love. What happened on The Love Boat stayed on The Love Boat.

In the film, Muriel moves to the city, makes a friend, finds a job, and gets a life. Then her friend is diagnosed with cancer, and Muriel becomes her nurse. “How can you stand this,” Rhonda cries one day. “You push me around in this chair, you cook for me, you even help me dress. I hate it!” Muriel differs. “When I lived in Porpoise Spit, I used to sit in my room for hours and listen to ABBA songs,” she says. “But since I've met you and moved to Sydney, I haven't listened to one Abba song. That's because my life is as good as an Abba song. It's as good as Dancing Queen.”

My heart leaps, just a bit. I shoot my friend the side eye. Is she feeling this as much as I am? I can’t tell. I keep my face neutral. I cannot reveal how much I, too, want my life to be as good as Dancing Queen.

In 1995, the technology that can map what this longing identification looks like in my brain does not yet exist. But if it had, here’s what it would have looked like inside my skull: my ventromedial prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain that thinks about the self — would be lighting up like crazy. Story does that to people: it gets them to become the characters they connect with. Muriel Heslop, c’est moi.

Forty-five minutes later, as the film draws to a close, I discover that I am not alone.

Muriel makes a lot of mistakes in the second half of the film, and her life definitely stops being as good as an ABBA song. She learns, though, and in the final scenes, she sets things right with her family. Then she goes to visit Rhonda, who has moved back to Porpoise Spit so that her mother can care for her. The frenemies are visiting, they are awful as ever, and Rhonda looks like she is living her worst nightmare, because she is. Muriel asks Rhonda to return to the city with her, Rhonda accepts, and just like that the two are racing to the waiting cab, rushing joyously into their shared future as Dancing Queen begins to play.

And here is where the wonderful thing happens. Everyone, and I mean everyone, in that theater starts to sing along with ABBA at the top of their lungs as Muriel and Rhonda escape Porpoise Spit. Arms sway overhead. Butts squiggle on seats. Voices rise and soar.

We are in an arthouse theater in a university town. We are an audience of sophisticates. We wear black. Our book bags bulge with heavy tomes. We are ironic and skeptical, and we dismiss the easy pleasures of popular culture as ideologically suspect. Except for now. Now, in this moment, together in this darkened theater with its sticky floors and musty seats, we are at one with Muriel, and we are at one with each other. We are a sudden choir of the uncool. We all know all the words and we are unironically having the time of our lives.

A century ago, the French sociologist Emile Durkheim called this joyous spontaneous unity “collective effervescence.” He associated it with religion, and saw it as central to our experience of the sacred. And that is what this was. We were enlarged by this film. It cracked us open, made us vulnerable, and then it glued us together again, better and more whole than we were before. We forgot ourselves watching the film, lost track of our worries, abandoned our inhibitions, and we gave in, together, to the transcendent joy of the moment. We were, in other words, swept away by story, just as nature means for us to be.

Princeton neuroscientist Uri Hasson is using fMRI technology to study how the brain responds to storytelling. During a good story, Hasson has found, the listener’s brain actually starts to look like the storyteller’s brain. The better the comprehension, the closer the resemblance – so much so that at times the listener’s brain actually anticipates what the storyteller is about to say. In such moments, the listener’s brain waves mirror the storyteller’s before the storyteller’s brain has actually created the waves that the listener will mirror. Hasson calls this “brain coupling,” and he says that it is “the neural basis on which we understand one another.” Human communication, he explains, is not the result of back and forth between people, as we tend to think. Rather, it “is a single act between two brains.”

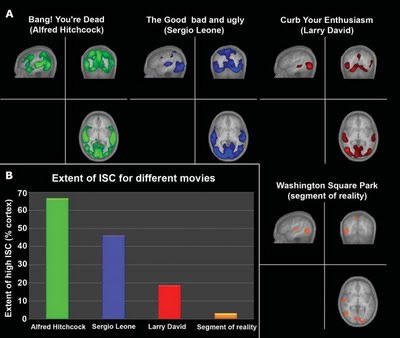

Story, Hasson has found, makes brains synchronize. And film and television extend and amplify the power of brain coupling: they are technologies of something I think we could call “mass synchrony.” Hasson put subjects in an fMRI machine and had them watch 30 minutes of Sergio Leone’s classic western, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. The film produced intersubjective neural alignment across 45 percent of the brain’s cortical surface. An episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents achieved 65 percent alignment. Larry David’s HBO comedy series Curb Your Enthusiasm produced a comparatively modest 18 percent alignment. As a control, Hasson showed subjects unedited footage of a crowd in a park. This generated a mere 5 percent alignment.

(source)

Sixty-five percent for Hitchcock is pretty impressive. But I am here to bear witness to a moment in a movie theater when, I would wager, intersubjective neural correlation verged on 100 percent. What happened at the end of Muriel’s Wedding was an absolute orgy of brain coupling, one that not only brought the audience’s brains into alignment, but also required us to overcome a significant amount of social inhibition to do so. The reward was immediate and real: a shared moment of simple joy that has stayed with me for nearly thirty years. I doubt I am alone in that.

Halfway through Dancing Queen, the film credits begin to roll. No one stands, no one rummages for coat and hat. No one leaves the theater. There is too much singing left to do.

How very amazing. The fMRI results harken back to the "Mind Meld" that the Vulcan Startrek character Spock performed, absent the "wire" of Spock's touch. It's kind of the mind's version of wireless internet!

Life is stranger than fiction. Or is it??

And ABBA! Yes, I still have ABBA's songs floating around in my head. Wonderful times.

Am late to read this, but so worth the wait!

I was dancing to ABBA in movie theatre aisles as Meryl , Pierce and Colin (first name basis - I felt so very close to them) brought Mamma Mia to my synapses! :)

Loved "collective effervescence" reference, it reminded me of Dr. Maria Nemeth's teachings (Mastering Life's Energies)

on the "luminosity" experience , during my Life Coach training during early 2000's.

One thing is very clear about this type of encounter, when it happens to you, you never forget it! And perhaps the brain even becomes attuned to replications at the nearest opportunity.:-)

A synchronous connection being recognized between us and other, a brain bridge in the ether, well I would even tag it as part of a "Mystikal" experience.

It is likewise very exciting to learn about the recognition of a neuroscience link around this subject, as you continue writing with The Story Rules Project!

PS- I'll have to ask you later about quoting some of your references, in my own personal "Mystikal" writing project. Ten years long in the process. :)