The Ghost of Christmas Now

Nondenominational thoughts on the day, with a little help from Dickens

It's that time of year when the fog around here becomes a thick heavy presence. It's not romantic and ethereal. It doesn't float lightly on the air in lovely misty wisps. The winter fog in southern Oregon is a substantial individual. It has a personality, an oppressive weight. It is like a demanding visitor who comes often and uninvited, makes itself comfortable, and then won’t leave. It is obtuse and difficult. It makes demands on your mood and your patience. It may stay for days, blocking the sun, the sky, the horizon, even, at times, the end of the driveway and the cherry tree at the bottom of the garden.

View from window, 7am, December 16, 2024

At such times, I think of Dickens, who began his novel Bleak House (serialized in twenty parts between March 1852 and September 1853) with an unforgettable description of the London fog. (Read it here, or — preferred method — have it read to you at the YouTube link below, starting at 5:47 and going to 8:50.)

For Dickens, fog is a penetrating civic distemper, a terrible, wet mood that settles upon the world, insinuating itself down throats and seeping into lungs, freezing fingers and pinching toes, blinding us and reducing us to a "groping and floundering condition,” one that is at once a symptom of existential malaise and a symbol of systemic corruption.

Dickens is particularly concerned, in Bleak House, with the bureaucratic horrorshow that was the English legal system in the mid-19th century: the fog is densest, darkest, and dreariest at Lincoln’s Inn, home of the high court. But the idea of fog as a bone-chilling image of total institutional non-transparency works very well now, too. According to a 2024 Pew study, fully 78 percent of Americans do not trust our government. And that was before election season, and the many betrayals of national trust that have unfolded in its wake.

All this ruminating about Dickens, distempered weather, and the moral fog of the moment got me to thinking about Christmas. Dickens is often credited with “inventing” Christmas, which is not quite true. What is actually true: he resurrected Christmas. When Dickens began writing novels in the late 1830s, Christmas had become irrelevant (mired in obsolete ancient ritual) and inconvenient (factories didn’t close on weekdays, and industrial workers did not get the day off). Then, in 1843, Dickens published A Christmas Carol, a ghost story about how the miserly Scrooge gets haunted into becoming a better, more giving man, and everything changed.

I. Writing to make money — and making meaning instead

Dickens was broke — not for the first time, and not for the last — and he wrote his seasonal ghost story in six weeks flat, driven by a naked need for profit. The Victorians loved ghost stories, and they especially loved them at this time of year. When the days were short, dark, and damp, when the nights were endlessly, awfully long, people would pass the time telling ghost stories. They would sit around the fire of an evening, and scare the Dickens out of one another. As it were.

Dickens delivered the ghost story of all ghost stories in early December of 1843. An instant bestseller, A Christmas Carol has been in print ever since. Over the centuries, it has made a pile of money. But — ironically — it didn’t solve the money problems that led Dickens to write it. So special was his story, the author felt, that it required a special binding, with gold leaf on the cover, gilded page edges, and four original illustrations. Production costs ate up the proceeds, and Dickens actually had to move his family to Italy for a time to avoid the debt collector.

If A Christmas Carol failed to rescue Dickens’ finances, it succeeded fabulously in reviving and reinventing the holiday for the modern age. When we say “Merry Christmas,” we are quoting Dickens, who made an ancient, abandoned greeting seem fresh and new. When we dream of a white Christmas, we are dreaming Dickens’ dream.

More to the point, when we think of Christmas as a time to give — to share what we have with those less fortunate than we — that, too, comes straight from Dickens. Christmas, Dickens wrote in A Christmas Carol, is above all "a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of other people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys." Dickens called this “The Carol Philosophy.”

II. Dickens is speaking to us across the centuries

Writing now, at a time when we are very much in need of a reminder — and a permission slip — to “open our shut-up hearts freely,” I am struck by how deeply contemporary Dickens’ Christmas wishes were. He wasn’t thinking of the holiday in particularly religious terms. For him, Christmas was less about obligatory sectarian observance than it was about voluntary secular openness. Dickens was ahead of his time in this: What he wanted to create, above all, was an occasion that would press us to practice coming together across our differences — an issue that was as much a problem in Dickens’ time as it is in our own.

When Dickens was writing, the cultural divide had a different configuration, of course. He was living in an England that cherished its rigid class system, and a London that was reeling with a new and unimaginably harsh kind of poverty. The population of London more than doubled between 1800 and 1850, from one million to 2.3 million souls. The vast majority of these were working-class people migrating in from a countryside where they could no longer live traditional, rural lives.

London wasn't set up for this influx — nor was any English city. There was no place to put the poor. Nor were there enough decent jobs to employ them. The result: people poured into the slums, crowding into collapsing tenements, several families often sharing single rooms. Those rooms were cold, damp, moldering, rat-infested, and crumbling. There was no clean water. No sanitation. No proper source of heat. Everyone was hungry. Disease was everywhere: typhus and typhoid, cholera and consumption, rickets and scurvy, smallpox and a ubiquitous, nonspecific “fever.” About 25 percent of babies born in the Victorian slums died before their first birthday. If you made it through childhood, you probably wouldn’t see forty. In London’s worst areas, the air was so bad that it sometimes made people pass out. Dickens was not one of these — he knew the London slums inside out. He walked them his whole life, wrote about them constantly, and liked to tag along with the police as they did their nightly rounds.

Alleyway in London slum

Poverty, suffering, willful blindness to poverty and suffering: these things were in Dickens’ mind when he wrote A Christmas Carol, in the hope that his story would encourage people to “to think of other people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.” I am struck by how much we need the same encouragement today. For if we’ve gotten a bit better about not seeing the poor as “another race of creatures bound on other journeys,” we are very much inclined to think of people whose politics differ from our own as less-than-human, and therefore as fundamentally undeserving of our attention, respect, or care. This sort of casual dehumanization is as dangerous now as it ever was. Almost half of Republicans and Democrats believe that members of the other party are not simply wrong — they are “downright evil.” Many believe those who disagree with them politically are not fully human, and that the country would be better off if large numbers of the opposition were to die.

Homeless woman providing child care, late 19th century

Dickens understood how easy it was to demonize people who were inconveniently different, but nevertheless deserved to be seen. He knew how quickly the heart could close, the courage it took to stay open. He saw it all up close, he breathed its terrible air and he did not lose consciousness. He brought what he saw into his books, beautifully and relentlessly, from the 1830s until his sudden death in 1870. He did so because he had once been the dehumanized one himself. He knew from his own boyhood experience of grinding want that most people will not see that which challenges them, that too many of us, when confronted with the failure of our worldview, will simply look the other way.

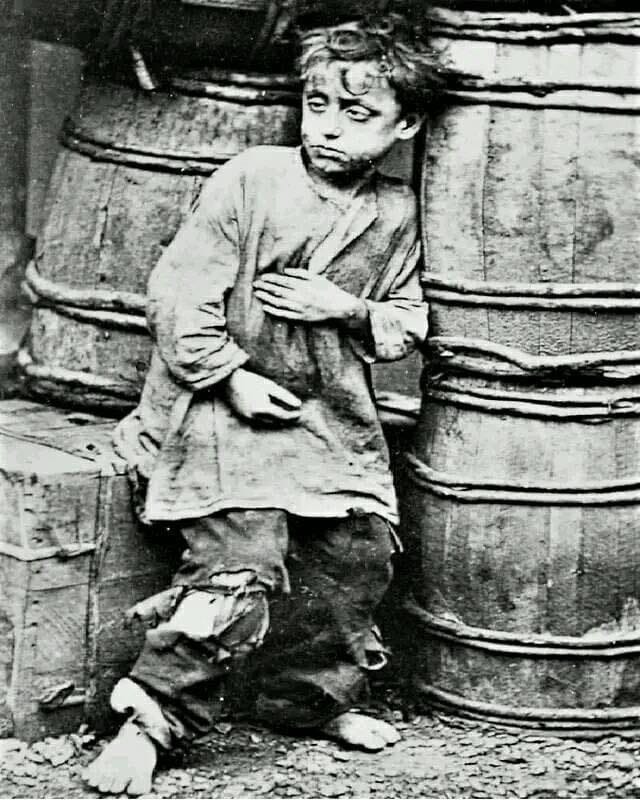

Homeless boy, Whitechapel, London

Dickens fought that attitude his whole life and he did it with storytelling. He gave us Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, Mister Pip and Nicholas Nickleby, Jo the crossing sweeper, Little Nell, and so many more besides — impoverished, abandoned orphans all. He did it not simply to entertain us, but to invite us to imagine our way into their experience, and so to grasp the fact of their humanity.

III. We aren't fully human if we aren't reading

Dickens believed that stories change consciousness. Now, neuroscience is backing him up. Reading, a new study reveals, reshapes the brain. The more you read, the more you reshape. And the nature of that reshaping reaches far beyond improving language skills. Someone who reads a lot, and reads well, is also cultivating the brain’s capacity for empathy and positive social connection.

That is amazing to think about. Reading may seem like a private, internal, solitary act — even a way of fleeing society. But it is actually the opposite. Reading is a profoundly social practice. When we read, we enhance our ability to understand the world and the people in it. We improve our capacity for empathy, for holding others in the warm embrace of understanding and care. When we don’t make reading a part of our life, we don’t develop that skill anywhere near as much as we could. We blunt ourselves as social beings. We harm our own humanity.

Last year, about half of all Americans didn’t read a single book. The numbers are even worse for young people. Many college students arrive on campus without ever having read a book from cover to cover. Professors report that they can no longer assign books, because even students at elite college and universities can’t get through them. This is more than a problem of declining literacy. More than a problem of distraction and vanishing attention spans. It’s a problem of disappearing personhood. Our political and social problems bear this out. Our failure to preserve reading in the era of social media has much to do with our hauntingly willing descent into thoughtless tribalism. If we read more, we would fight less.

Everybody read Dickens, even people who could not read. Families read his works together around the fire at night. The poor scrounged for pennies to hire someone to read Dickens to them while they worked. Dickens himself did hundreds of public readings, performing his works to sold-out audiences in Britain and America. His 90-minute version of A Christmas Carol was among his most favored shows. After a particularly powerful show in Boston — during which the rapt audience laughed and cried as Dickens did every character voice, every facial expression, every physical gesture — the city spontaneously recovered from its long Puritan hangover and began celebrating Christmas. Dickens’ impact on the people of Boston was so strong that to this day, his ghost is said to haunt the Parker House hotel, where he stayed.

Dickens’ actual performance copy of “A Christmas Carol.”

IV. Read like your life depends on it, because it kind of does

This holiday season, my gift to you is a challenge — and an invitation: Read. Make time for it. Read on your own. Read together. Gather around the fire or the Zoom screen and pass a book around, everybody reading aloud as much or as little as they like. Pause wherever you want to — remark on whatever strikes you —then continue. Go around the circle until you’re done.

Maurice and I did this with high school students the year we taught at a boarding school (another story for another day). I did it with Ivy League college students, too. It was a new thing for most of them. Everyone loved it. No one thought it was childish or boring. They loved reading out loud together because humans love sharing stories in real time. It’s one of the things that we do and that we need. We’re wired for it, we require it, but we’ve forgotten that. It’s time to remember.

So, if you are still reading this, make some time, as the year comes to a close. Use that time to sit around with family and friends and read to one another. Maybe you read A Christmas Carol. Maybe you read other Victorian ghost stories. Or one of Dickens’ other Christmas stories. Maybe you read something else entirely. Whatever it is, just do it and do it together. Live a story together in real time. Let it be a delight in itself — and let it be a beginning. Let it be something you carry with you into a very happy new year.

Linked at Chicago Boyz:

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/72719.html

Loved this and loved the opening of Bleak House, too. Amazing writer. Thank you! Merry Christmas 🎁🎄!