I was working on a post about storytelling, love, and the neuroscience of human connection — and then world events took a terrible turn and my thoughts turned, too. I began to think about hate. What is hate? Why do we experience it? What can we do, if anything, to prevent it? What can we do, if anything, to make it go away, when it arises? Can we eliminate hate, or is it one of those conditions we must learn to live with, like chronic pain or an incurable disease?

I have been taking walks and ruminating on these questions. I have been reading and googling. And what I have discovered in my effort to get clear on hate is that there just isn’t a ton of clarity about what hate is. It’s not for lack of effort — people have been trying to nail down the hate problem for thousands of years.

Here’s Aristotle, writing 2500 years ago: “Anger is always concerned with individuals … whereas hatred is directed also against classes: we all hate any thief and any informer. Moreover, anger can be cured by time; but hatred cannot. The one aims at giving pain to its object, the other at doing him harm; the angry man wants his victims to feel; the hater does not mind whether they feel or not.” Hatred, according to Aristotle, is defined by contrast: it’s worse than anger, and more enduring; it targets groups and members of groups; it seeks to harm, and it is entirely lacking in empathy or care. Worst of all, there is nothing we can do about it. Hatred “cannot be cured” — it is simply a part of the human condition, the part that, if unchecked, could well destroy humanity itself.

Getting a handle on hate is perhaps the most pressing and urgent problem we face. As University of Amsterdam psychologist Agneta Fischer wrote in 2018, hatred is “the most destructive affective phenomenon in the history of human nature.” And yet, the science of hate is very far from settled. Researchers can’t even agree on whether hate is an emotion, an attitude, a syndrome, an evaluation, a judgment, an intense version of anger, or — most chillingly — an excuse. Our understanding of hatred is in many ways still the understanding of Aristotle — a definition, a despairing description that allows us to identify hate, but gives no real guidance about how to mitigate or manage it. As a 2023 article in Neuroscience put it, hatred is “intense dislike that encourages the elimination of others [and] involves dehumanization, or the denial of human qualities to others.” According to that same article, “Despite the importance of understanding the neuropsychiatry of hate, clinicians and investigators have devoted relatively little effort to its study.” We know hate when we see it — and right now, as a world, we are seeing it. But we don’t really understand it, and because of that we can’t do much about it, and because of that, we are extraordinarily vulnerable to it.

Hatred centers on making it psychologically permissible to annihilate people. That much we know, and have long known. What we need now is a proper scientific understanding of hate. Until we have such an understanding, we will not be able to develop tools to deal effectively with hatred, and hatred will continue to hold us hostage, both literally and figuratively.

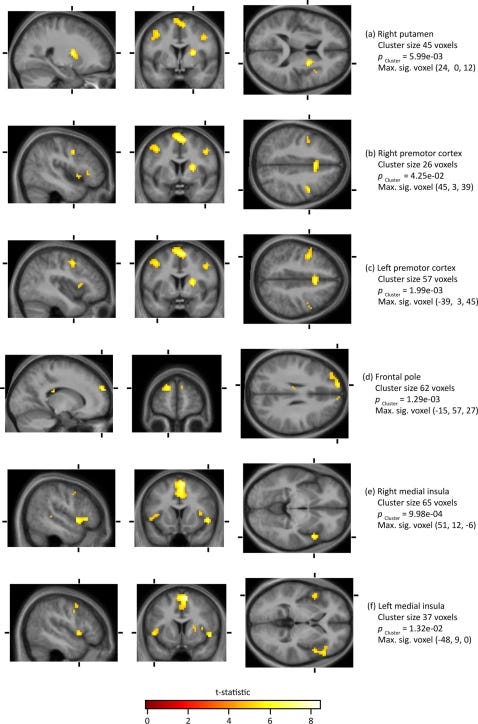

Understanding hatred scientifically begins with understanding how it arises in the brain. Turns out that hate has a well-defined neurology. In 2008, scientists wanted to see what happens in the brain when we experience hate. So they put people in fMRI machines and showed them photos of people they hate alongside photos of people about whom they felt neutral.

Source: Semir Zeki and John Paul Romaya, “Neural Correlates of Hate,” PLoS One 2008.

Seeing the face of a hated person reliably activated several areas of the brain: the medial frontal gyrus, right putamen, the premotor cortex, the frontal pole, and the medial insula.

Source: Semir Zeki and John Paul Romaya, “Neural Correlates of Hate,” PLoS One 2008.

The more the hate, the greater the activation. The activation pattern was distinct from what happens in the brain when we experience fear, anger, aggression, and danger. Hatred is not a variant of these emotions, then, but is its own thing. Hate is associated with feelings such as contempt and disgust and it prompts us to be highly reactive to these feelings. Hate activates us, and not in a good way. It’s a sort of ever-intensifying circuit, one that goads us to combat, to attack or defend.

Worse: hate is associated with pleasure. One study found that when watching members of an opposing group suffer, the ventral striatum — the part of the brain that experiences reward — lights up. We are actually built to enjoy the spectacle of our enemies’ pain. That pleasure is the prize our brains give us for hating.

So what does this mean? It means, for one, that we are hard-wired for hate. Hate has a distinctive neural signature. It is written on our brains, etched deep by millions of years of evolution. If it is a dangerous and ugly way of being, it is also a very human way of being. Why? Why would evolution do this to us? What possible value could hate have for the survival of the species?

MIT cognitive neuroscientist Rebecca Saxe believes that our capacity to hate is an inevitable, if unfortunate, by-product of our tendency to to think in us-them terms and to divide ourselves into “in groups” and “out groups.” We are innately tribal, and that has everything to do with how much we have historically needed others for our own survival. As extraordinarily social animals, we depend upon the group — the family, the tribe, the village — for our safety and wellbeing. Within the group, we care, we share, we cooperate and collaborate. Love and empathy live within the group. There is also loyalty to the group when it is challenged from beyond — which means we need to be able to see humans, or groups of humans, who are not from our tribe as expendable when our own survival is on the line. Hate makes this peculiar doublethink possible — it is at its core a mechanism for refusing to recognize the humanity of other humans. It allows us to objectify, dehumanize, and destroy. Hate makes it possible to define certain humans as not-human — and then to eliminate them without psychic cost.

One might imagine that hatred evolved as a sort of psychological support system, a necessary evil in a prehistoric age of small tribes competing for scarce resources. My tribe needs to eat; if your tribe is taking food we need for ourselves, we may have to wipe you out in order to survive. The capacity to hate makes that a tolerable idea. But recent studies show that isn’t actually what hatred is about or for. Hate is less about resources than about values.

One recent study found that we are more likely to hate the person whose worldview threatens ours than we are to hate the person who got the thing we wanted, or won the prize we sought. The more different the other person’s beliefs are, the more we hate them. As Dutch researcher Cristhian A. Martinez observes, “participants expressed significantly more hate toward individuals endorsing views that were opposite to their own on issues such as abortion, the legalisation of drugs, or same-sex marriage than toward individuals who blocked their goals and caused them to lose a reward. This could indicate that at least part of what people find particularly aversive about their hate targets is the perception that those individuals or groups endorse the opposite of what they believe is fair, noble and right, or their idea of what is a good life or a good society.”

Hate, in other words, is philosophical. It is a neurological circuit centered, ultimately, on eradicating threats to our ability to make moral sense of our own lives. Such threats can only come from other humans, from people who think differently from us. Hate makes it okay to annihilate existential threat by annihilating the people whose thoughts pose that threat; it does so by enabling us to see people as not-people.

This is ugly in the extreme, and if it is understandable from the perspective of evolutionary biology, it’s also something we urgently need to master. Human flourishing depends on it. Human survival depends on it.

The Story Rules Project was created to study how story can help heal America’s toxic partisan divide. Political polarization in the US, we have noted, has reached a point where people on both ends of the spectrum willingly state that they don’t see those on the other side as fully human, and would not mind if many of them died. Read that again: Americans on both ends of the political spectrum do not regard their ideological opponents as human, and would not object if they were exterminated. Recall the definition of hatred offered here: a mental process that involves dehumanizing others as preparation and justification for destroying them. Polarization, viewed through this lens, is simply a fancy word for describing the process by which America is becoming fractured by hate. The way we live now: this is what hatred looks like when it gets encoded within the two-party system. On issue after issue after issue, we are stalemated, stuck in a doom loop that is undermining our institutions, shredding our civic culture, poisoning our values, ruining relationships, and even breaking families apart.

Over the past couple of weeks, we’ve been reminded of just what is at stake when hatred festers unchecked. It is so easy to stoke it and weaponize it, so simple to unleash the will to annihilate others, so hard to stop it once it starts. Over the past couple of weeks, we’ve also been powerfully reminded of our purpose. When we say we are studying how stories can help us heal from polarization, what we’re really saying is that we’re working on the problem of how to mitigate — or even eliminate — hate before it’s too late.

If hatred is, at its essence, a technique of dehumanization, that means it arises in the absence of empathy. Empathy is our social superpower — it allows us to grasp and even share the feelings of others, to connect deeply on an emotional level, and so to know them as fully human. It follows that the remedy for hatred, the way to short circuit it, may be to create empathy where none exists — and to do so on a mass level. This is where storytelling comes in.

Stories, as we’ve shown, are engines of empathy creation. When we connect with characters, we become them. Characters are our avatars in the virtual reality machine of story; we live their fictional experiences as if they were our own lives. We can watch the brain do this: a brain immersed in a great story looks exactly like a brain living the events of the story. Great immersive stories can also synchronize our brains — my brain and your brain watching a Hitchcock film or a spaghetti Western are likely to look very similar. We are wired for story because story can wire us to one another.

Stories do more than let us practice empathy. They also allow us to do so at the level of abstraction, which means that stories allow us to empathize at scale. Story ensures that we can feel close to people we don’t know, that we have never met, that we will never meet. These fictional people may be very different from us — they may live in a different time or place, have different values or beliefs, be a different race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, or gender. They may be Harry Potter or Harriet the Spy, Odysseus or Antigone, Jane Eyre or Juliet, Clarice Starling or Stringer Bell or Scout, Walter White or Sethe or Tony Soprano. The things that so easily trigger hate in the real world — differences of value, belief, identity — invite connection in the world of story.

Story is an antidote to hate.

Story jumpstarts empathy — without story, our only way to connect deeply with others would be through personal contact. With story, we can connect with infinite others and we can do it across time and space. Stories make us bigger — expanding and stabilizing our sense of who we are, of what ideas and ways and beliefs we can encounter and still be strongly, securely ourselves. In this way, stories grow our capacity for community, dissolving the usual us-them divides and offering us a vision of group identity that is powered by belonging rather than division, by love rather than hate. And that, in turn, can generate the kind of moral clarity that changes the world. This is what Abraham Lincoln meant when he called Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.”

We are in need of transformative moral clarity now, more than ever, in so very many ways. To arrive at that clarity — to get there in body and soul — we need powerful, intentional storytelling, storytelling inspired by the desire to unite, storytelling that grabs us by the brain and brings us into virtual communion with others across our differences. There is a chemistry to such storytelling that is as old as we are, and that holds within it our potential to be a far better humanity. All we have to do is use it.

More, much more, in future posts.

Crucial topic!

Questions this thoughtful piece evoked: Do animals experience hate? Does a natural prey animal illicit hate in the predator or are they just seeing food? Do rival packs/troops experience hate toward their rivals? If not, is hate a defining aspect of being "human?" When someone becomes disillusioned with a hateful group and leaves it, what happens to their hate? If you switch allegiance between groups, does hate change in any way? Immediately after the 9/11 attack, many hostile groups came together against the aggressors. Does redefining groups change or defuse hate? There is so much more to understand. We all need to studying and learning about this topic.

Erich Maria Remarque's novel 'The Road Back' follows a group of German soldiers after the end of the First World War--it is kind of a continuation of his All Quiet.

Shortly after peace is declared, the narrator, Ernst, is on his way home. He passes an outdoor field hospital--gas cases, men in very bad shape who cannot be moved. They beg, 'take me with you', but nothing can be done. Ernst is depressed by the sight, but a little later, he feels his spirits returning, and his heart soars with great hopes for the new era of peace.

Then he feels guilty...how can he be happy when his comrades are dying in hopeless misery?..and he muses: "Because none can ever wholly feel what another suffers--is that why wars perpetually recur?"

Part of the answer, I think, but not the whole answer...empathy for the suffering (real or imagined) of those on one's own side is almost equally a factor in the outbreak of wars.