Your brain thinks disagreement will kill you

We experience political challenge as an existential threat

Your name is Emily, and you are fourteen. Shy. Awkward. A little anxious. You are surrounded by other fourteen-year-old girls. Some are also shy, awkward, anxious. Some are not. You all look the same, sitting at your school desks in your plaid skirts and collared shirts. But you are not the same. You can't speak for what your classmates are thinking as they gaze at the teacher or stare out the window, as they take notes, snap their gum, drift into sleep. But you can speak for you, and you know you are different. You have known this for some time. You are a performer. You are born to act. Your parents put you in acting lessons to help you with your anxiety, and it did help. It also showed you who you are, or at least who you could become, if you had the chance.

But you don’t have the chance. Not really. It’s a very long way from Phoenix to Hollywood. Six hours, each way. If you want to go on casting calls, that's a problem. And if you can’t do casting calls, you can’t become an actor. You can’t become who you are. It would be so much easier to be in L.A. But you aren’t in L.A. And that’s a problem. And so on, as your mind travels around the same old track, thinking the same old thoughts, again and again. Until it doesn't. Until, in a flash, you see a way.

That night, you invite your parents into your bedroom. They perch on the edge of your bed as you deliver a presentation laying out all the reasons why you should be allowed to move to Hollywood to pursue your as-yet non-existent acting career — not some day, but RIGHT NOW. You are measured and serious, as professional as you know how to be. You have PowerPoint slides. You even have music: Madonna’s Hollywood plays softly as you speak, its irony crushed by the weight of your conviction.

Your parents find your argument compelling. You are right — so right that they promptly uproot their lives to honor how right you are. You move to Hollywood. You change your name. You go to casting calls. You get small roles, and then you get big ones. You get nominated for Golden Globes and Oscars, and then you win them. You are who you dreamed you could be, when you were a fourteen-year-old Catholic school girl, sitting in class, dreaming of La La Land. You live happily ever after, so far.

This is not a believable story, but it is a true one. It belongs to Oscar-winning actress Emma Stone, and she’s been telling it over and over again, for many years.

Stone calls it the story that will never die. People just keep asking for it. She’s told it at the request of Jimmy Kimmel and Graham Norton; she’s told it at press conferences and on the red carpet; she’s told it to the New York Times, The Hollywood Reporter, and ABC News. Even though interviewers already know the story, they cannot hear it too many times. It’s adorable, yes, in a Young Sheldon meets Shark Tank sort of way, to think of earnest Emma pitching her dream and asking her parents to invest in her. But there’s more to this story’s longevity than that.

My hunch is that this story doesn’t die because it taps into a very specific shared cultural fantasy — that reasoned argument is the key to getting what we want out of life. We like to believe that we can amass facts and use logic to persuade people that their point of view is wrong and ours is right. This is what we learn in school. Our major institutions are grounded in this belief, and so are our nation’s founding documents. Emma Stone’s story won’t die, I suspect, because it offers such whimsically lovely support for the idea that if we can just make the right argument the right way, we can bend the arc of history — not to mention our parents — to our will. We love the idea even though we all know, deep down, that life is not like this, that — with the possible exception of Emma Stone’s parents — people are not like this.

According to organizational psychologist Adam Grant, if we think argument is the way to persuade, we had better think again. No one wants to be around a “logic bully,” Grant warns: “Hammering people with facts rarely wins the argument and sometimes loses the relationship. Whether you’re preaching, prosecuting or politicking, you’ve already concluded that you’re right and they are wrong. You’ve flipped a switch that shuts down your capacity for critical thinking.” Grant is talking about the psychology of argument here: the mind of a person driving a forceful argument is a closed mind. Argument is not an appeal. It is not an invitation to dialogue. It is, on a rhetorical level, an act of force — a “hammering” — whose goal is not mutual understanding or compromise, but to win.

People know when they are being hammered by a closed mind, Grant explains, and in response, their minds close down as well. Numerous studies have shown that we tend to resist direct challenges to their beliefs, especially when those challenges strike at our identity. The more important the belief, the less willing we are to give it up — so much so that we often double down, becoming more confident that we are right when presented with factual evidence that we might be wrong. This pattern is especially strong when it comes to politics.

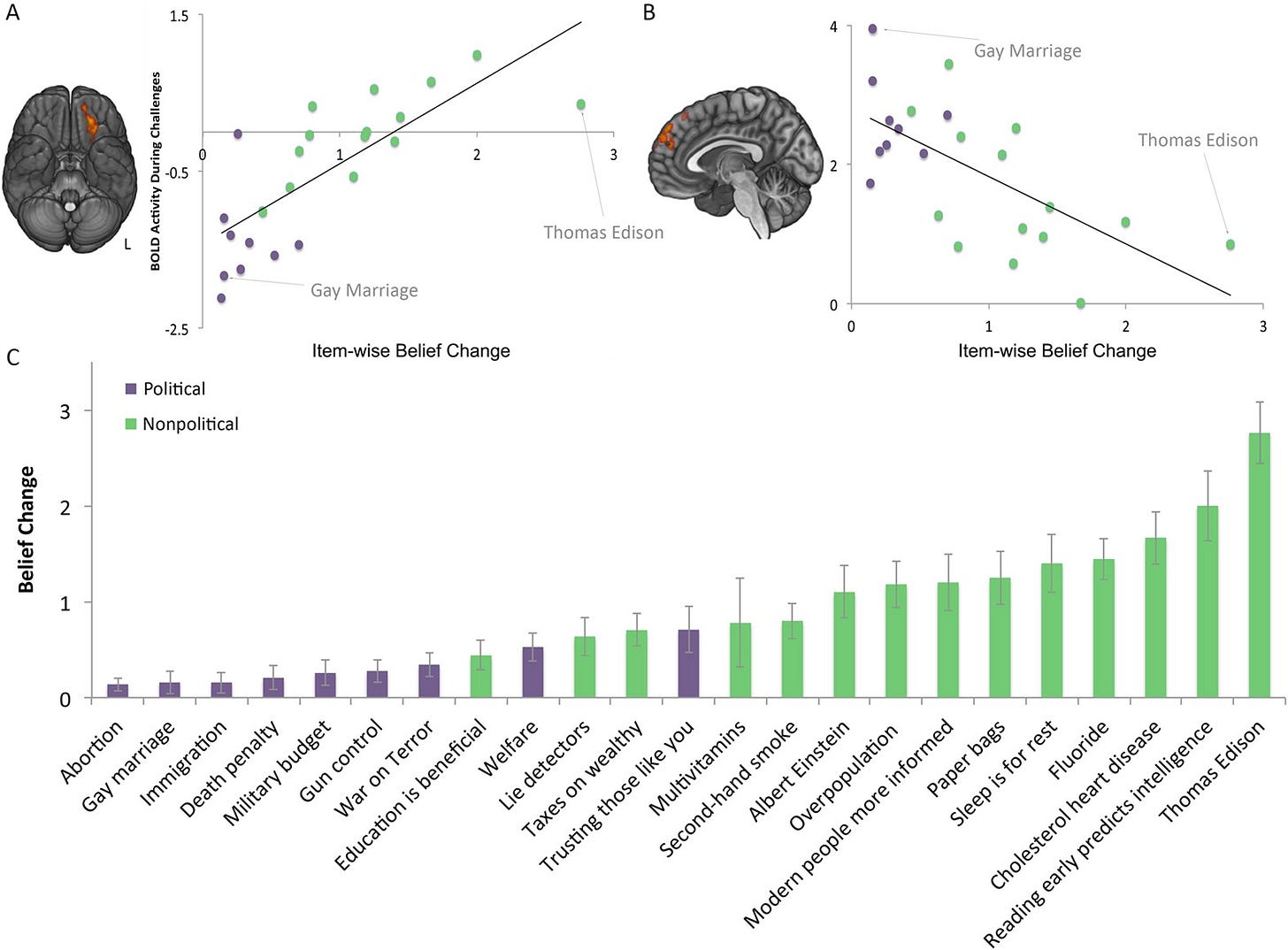

Neuroscientists Jonas T. Kaplan, Sarah I. Gimbel, and Sam Harris wanted to see what the brain looks like when “maintaining belief in the face of counterevidence.” So they gathered forty self-identifying, committed liberals, put them in fMRI machines, and watched how their brains reacted to statements that undercut their views on both political and nonpolitical subjects. They began by showing subjects “identity-consistent” statements to establish a baseline. For political beliefs, these included: “Abortion should be legal”; “taxes on the wealthy should be increased”; and “the laws regulating gun ownership in the U.S. should be made more restrictive.” For nonpolitical beliefs, these included: “taking a daily vitamin generally improves one’s health”; “Thomas Edison invented the light bulb”; and “fluoride helps prevent tooth decay.”

Then they showed subjects “challenge statements” — compelling, but not necessarily true claims that contradicted their baseline beliefs. For instance, the political belief that the U.S. should make gun laws more restrictive was contradicted with statements such as: “98% of gun crimes are committed with stolen guns. People who possess guns illegally are unlikely to obey new laws regulating gun ownership.” Similarly, the nonpolitical belief that Thomas Edison invented the light bulb was countered with statements such as: “Edison's patent for the electric light bulb was invalidated by the US Patent Office, who found that it was based on the work of another inventor.” After reading the counterarguments, study participants were shown the original identity-consistent statements once more and asked about their “post-challenge belief strength.”

The study showed that subjects were far more willing to change their beliefs when challenged on topics they did not regard as political. Subjects readily revised their beliefs on light bulbs and vitamins. But when it came to hot-button wedge issues such as abortion, immigration, and gun control, they were very resistant to change. The fMRI results left no doubt as to why.

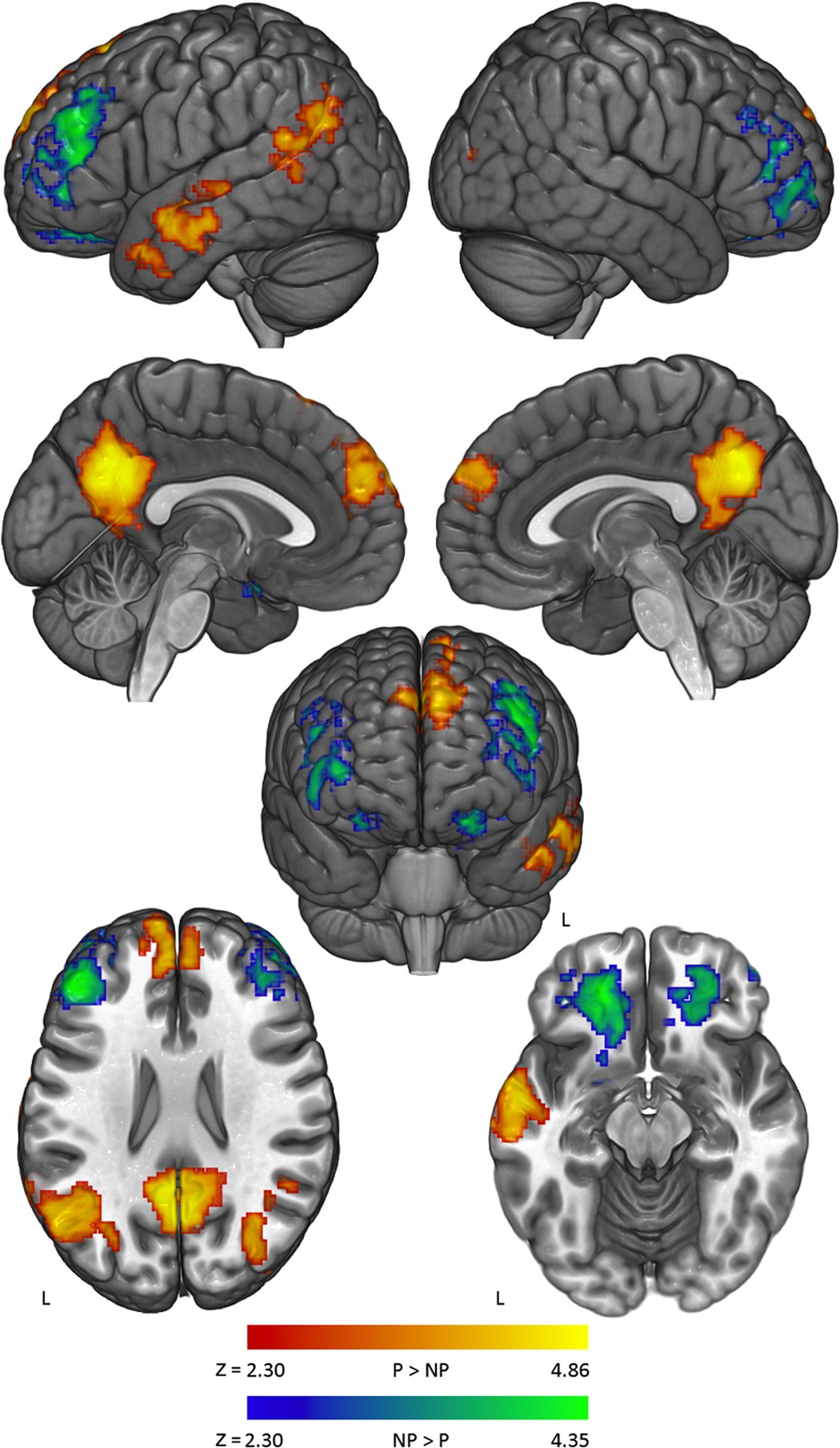

The red-yellow areas show the brain responding to political challenge. The amygdala is the big yellow hot spot right in the center of the brain. The blue-green ares show the brain reacting to nonpolitical challenge. Source.

Challenges to political beliefs activated the amygdala, the part of the brain that detects danger. In the words of the investigators, the subjects’ amygdalas may be “signaling threats to deeply held beliefs in the same way they might signal threats to physical safety.” The study’s participants were going into fight-or-flight mode when faced with statements that did not align with their convictions. Their hearts sped up. Their breathing got fast and shallow. Their pupils dilated and their muscles tensed. They were braced for attack. They were, in other words, experiencing political argument as a matter of life and death.

This finding explains a lot. It tells us something vital about why we have become so polarized, and also why polarization seems to be getting worse the more we try to reason, argue, and debate ourselves out of it. Both sides feel attacked; neither side is open; every one is “hammering” everyone else and everyone is shutting down.

Our political convictions are central to our sense of who we are — and when those convictions are challenged, we experience it as an existential threat. If our beliefs are wrong or illegitimate, so are we. We can’t have that. And so we double down, fending off opposing ideas as if they were physical attacks — because, according to our brains, they are. This is natural, inevitable, and protective. It’s also a huge problem.

“Few things are as fundamental to human progress as our ability to arrive at a shared understanding of the world,” the investigators write; “the inability to change another person’s mind through evidence and argument, or to have one’s own mind changed in turn, stands out as a problem of great societal importance. Both human knowledge and human cooperation depend upon such feats of cognitive and emotional flexibility.”

And here, in the shape of a brain scan, we have a defining paradox of free society, at least as we have understood it for the past 250 years. We must be able to air our ideas and disagree; we must be able to tolerate differences of opinion and belief so that the best ideas, the ideas that offer us the most opportunity for flourishing and happiness, can be discovered. Persuasion is critical to this process, as are compromise and collaboration. And yet our approved mechanism for testing ideas — reasoned argument and vigorous debate — may actually be, biologically speaking, fatally flawed. It may actually be driving us apart, producing the polarization that presently threatens our republic.

This is why we are in a “doom loop,” which political analyst Lee Drutman defines as a “self-reinforcing dynamic in which … the more the two parties take strongly opposing positions, the more different they appear. And the more different they appear, the more the other party comes to feel like a genuine existential threat to the other.” This is why over 40 percent of Republicans and Democrats believe that members of the other party are not simply wrong — they are “downright evil.” This is why about half that number believes members of the other political party are not fully human, and that the country would be better off if large numbers of the opposition were to die. This is why 19 percent of voters report that politics has hurt their friendships and family relationships. And it is why we can’t even agree on basic facts.

We are living in a civic Catch-22 of epic proportions: we urgently need to stop the doom loop death spiral, but when we try to reason our way out of it, we just make it worse. We need persuasion by other means. We need a nonthreatening mechanism for rediscovering our mutual humanity, and for coming together across our differences to solve our most intractable, politically fraught problems.

The answer lies in story, and specifically in what we might call post-partisan storytelling. More on what that is and how it works in the coming weeks.

"Prophecy masquerading as reason", now that's a powerful keeper! :)

In business disagreements / arguments / political warfare, I've found it very useful to state my opponent's view as clearly as I can, ask him if that hits his main points, and then respond.

I think it would be very, very valuable to have formal debate as a standard part of the high school curriculum. Probably not feasible with the public schools as politicized as they now are, though.